Where Did the Apollo Astronauts Land? A Guide to NASA’s Historic Moon Landing Sites

October 10, 2024

During the Apollo program, astronauts from six missions landed spacecraft on a range of carefully selected lunar sites. NASA administrators chose each landing site with specific scientific and operational objectives in mind. Early missions, like Apollo 11, prioritized safety, selecting relatively flat and even terrain such as Mare Tranquillitatis for a smooth landing and takeoff. As the program progressed, later missions ventured into more challenging landscapes, such as rugged highlands and steep valleys. Each mission helped humanity learn more about the Moon's geological diversity. Scientists studied Apollo’s findings to understand lunar volcanic plains, impact craters, and more. Want to know exactly where the Apollo astronauts touched down and what made each location unique? Read on to discover the historic sites that shaped our understanding of the Moon.

Mare Tranquillitatis, or the "Sea of Tranquility," is a vast lunar plain located on the Moon's eastern hemisphere, spanning approximately 876 km across and covering 436,000 square kilometers. Its surface lies 1,390 meters below the surrounding highlands, giving it a sunken appearance. This dark, basaltic plain formed from ancient volcanic activity, with lava filling the basin after massive impacts billions of years ago. Its slightly blue hue, rich in iron and titanium, is a striking contrast to the surrounding lunar surface. Named by Italian astronomer Giovanni Riccioli in 1651, Mare Tranquillitatis is centered at coordinates 30.8°E, 8.4°N. The flat and smooth terrain made it an ideal site for Apollo 11’s historic landing in 1969, where humanity first set foot on another world.

Oceanus Procellarum, or the "Ocean of Storms," is the largest of the lunar maria, located on the western edge of the Moon's near side. Spanning 2,500 km across and covering an area of approximately 1.7 million square kilometers, it is the only lunar mare designated as an "ocean" due to its immense size. The region lies about 2,000 meters below the surrounding terrain, formed when ancient volcanic activity filled the basin with dark basaltic lava. Its mineral-rich surface, high in potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus, makes it unique among the lunar maria. Named by Giovanni Riccioli in 1651, Oceanus Procellarum is centered at coordinates 57.4°W, 18.4°N.

When Apollo 12 landed here in 1969, it touched down just 160 meters from NASA's Surveyor 3 spacecraft, which had landed two years earlier. The Apollo 12 astronauts retrieved parts of Surveyor 3 for scientific study, including its camera, offering scientists a chance to study the effects of long-term exposure to space.

Fra Mauro is a prominent lunar highland region located in the Moon's southern hemisphere, spanning 95 km in diameter. This ancient impact crater is heavily eroded, with its floor littered with debris from the massive Imbrium Basin impact. The crater is approximately 0.9 km deep, making it shallower than many well-preserved craters. Geologically significant due to the presence of ejecta from the Imbrium impact, it provides key insights into the Moon's early history.

Originally selected for Apollo 13, the Fra Mauro site became the landing area for Apollo 14 in 1971, where astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell landed just 200 feet from their intended site. The region was chosen for its geological richness, offering scientists the opportunity to study material ejected from deep within the Moon during the Imbrium event. Shepard and Mitchell conducted two moonwalks, aided by the Modular Equipment Transporter (MET) to haul tools and samples. During their second extravehicular activity (EVA), they explored the nearby Cone Crater and collected "Big Bertha," a massive 20-pound breccia. This sample, along with nearly 100 pounds of lunar material, has provided critical insights into the formation of the Moon and possibly even Earth.

Hadley-Apennine is a rugged lunar region located near the southeastern edge of Mare Imbrium, adjacent to the towering Apennine mountain range. The Apennines rise dramatically, reaching heights of up to 5 km, forming one of the most visually striking landscapes on the Moon. This area is also home to Hadley Rille, a 120-km-long sinuous channel likely formed by ancient volcanic lava flows. Apollo 15, the first mission designed for extended surface exploration, landed near this geologically rich site in 1971.

Astronauts David Scott and James Irwin explored the region using the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV), covering over 27 kilometers during their three moonwalks. Their main objectives were to sample volcanic material from Hadley Rille and gather rock samples from the slopes of the Apennine Mountains. Among the most significant finds was the "Genesis Rock," a sample of ancient anorthosite that provided insights into the Moon’s early crust formation. The astronauts also deployed the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), which included instruments to measure seismic activity, the Moon’s magnetic field, and heat flow from its interior.

The Descartes Highlands is a rugged, elevated region in the Moon's central highlands, marked by its heavily cratered terrain and ancient geological features. Spanning about 50 km in diameter, the region is composed of fractured and brecciated rock, with much of the surface dating back over 4 billion years. Named after the French philosopher René Descartes, the highlands were selected as the landing site for Apollo 16 in 1972. The primary mission objective was to explore two formations, the Descartes and Cayley, which scientists initially believed were of volcanic origin.

However, astronauts John Young and Charles Duke’s exploration revealed something surprising—samples they collected showed no evidence of volcanic material. Instead, they found that the region’s surface was formed by ancient impact processes, reshaping scientists’ understanding of the lunar highlands. The astronauts conducted three EVAs, during which they explored features such as the slopes of Stone Mountain and the rim of North Ray Crater, collecting 209 pounds of rock and soil. One of their key scientific contributions was deploying the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), which included seismometers, a heat flow experiment, and a cosmic ray detector. Apollo 16 was also notable for deploying the first telescope on the Moon, the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph, to observe astronomical phenomena.

The Taurus-Littrow Valley, located on the Moon's southeastern edge of Mare Serenitatis, is a deep, narrow valley flanked by towering mountain ranges, including the North and South Massifs, which rise to 2,000 meters. This region, selected for Apollo 17 in 1972, offered a diverse geological landscape, featuring a mix of ancient highland material and volcanic deposits. The Apollo 17 mission, the last of NASA’s crewed Moon landings, aimed to gather samples from both the highland formations and younger volcanic features.

Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt, the first trained geologist to set foot on the Moon, explored the valley’s dramatic terrain. During their three EVAs, they collected 254 pounds of rock and soil, including samples from Shorty Crater, where they discovered the famous “orange soil.” This material turned out to be volcanic in origin, providing evidence of volcanic activity early in the Moon's history. The mission's scientific experiments included deploying the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) and conducting studies of the Moon's seismic activity and heat flow. Apollo 17 remains notable for breaking several records, including the longest lunar surface stay and the largest amount of lunar material collected.

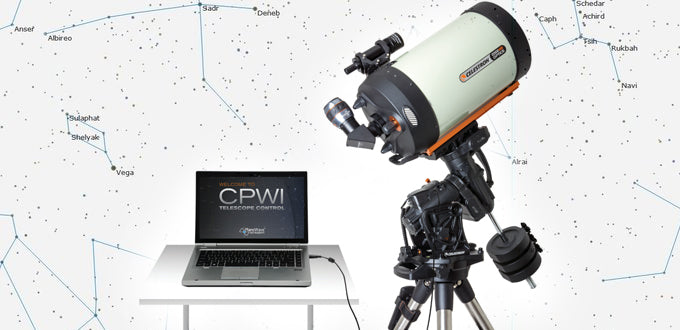

The Apollo missions not only revealed the Moon’s rich geological history but also left a legacy that amateur astronomers can appreciate firsthand. With each glance through your telescope, you can trace the journeys of the Apollo astronauts—from the tranquil plains of Mare Tranquillitatis to the rugged highlands of Taurus-Littrow. Each region, visible as subtle features on the lunar surface, connects us to a historic mission and the scientific discoveries it brought home. So next time you gaze at the Moon, let your telescope transport you to the very spots where humans made history, and imagine what future explorations might uncover.